One-hundred-and-seventy people died of an overdose in B.C. in May 2020.

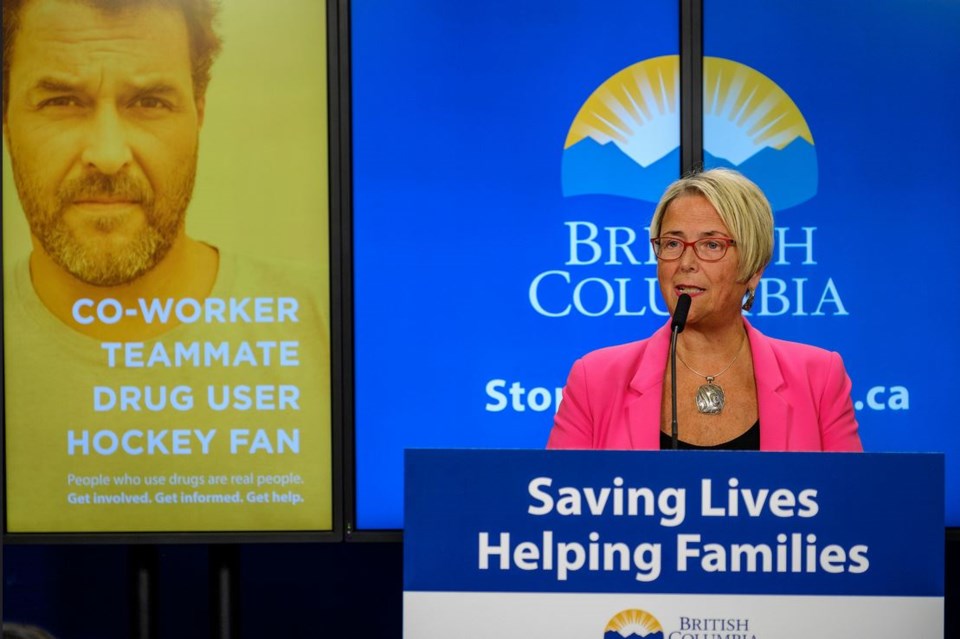

This is alarming. Recently, Mental Health and Addictions Minister Judy Darcy publicly announced a proposed change to BC Mental Health Act legislation to allow what she described as “a new part ... to provide short-term stabilization care for a youth in the immediate aftermath of an overdose.”

The change would allow for the two-to-seven-day detainment of a person under the age of 19 who experiences an opiate overdose.

This proposed strategy is presented as one solution to the complex problem of opiate poisonings of B.C. youth who use substances. However, better help for youth must involve more than a legal mechanism for health-care providers to involuntarily hold them in a hospital setting.

There is a glaring mismatch between the intended benefit of creating a voluntary recovery plan and the potential harms of detaining a youth while health-care professionals create the plan.

Many youth-focused mental health and substance use clinicians are wondering exactly how this change can enable better services and increase engagement of a disenfranchised and stigmatized group.

Shockingly, the voice of youth who use substances is missing from this public conversation.

In all age groups, the number of people involuntarily admitted to hospital by way of the BC Mental Health Act has been steadily increasing. Involuntary admission can be experienced as punitive, traumatic, paternalistic, and a violation of rights and autonomy.

This can cause lasting harm and disconnect people from a system meant to help.

Currently, the MHA has specific criteria that must be met for forced hospitalization. With the proposed change in legislation, those under 19 and arriving in hospital following opiate poisoning will meet criteria for involuntary admission.

We must ask, what is the potential long-term damage if a breakdown of trust and safety in the system deters youth from voluntarily seeking help in the future?

The crucial therapeutic relationship between health-care provider(s) and patient requires a collaborative and trauma-informed approach to engage youth. Coercive care at a highly vulnerable time can negatively impact future healthcare relationships.

Developing treatment plans may be the goal, however, the outcome of a short-term forced hospitalization is more akin to substance detox. Importantly, there is a higher risk of fatal overdose in the first days after detention or treatment because abstinence from substance use for a period of time decreases opiate tolerance.

And then, because of previous negative and/or traumatic experiences, they or their peers might avoid seeking medical care for fear of detainment.

Parents and families are scared and desperate for help. They have been vocal about the lack of available and accessible services for youth living with substance use issues.

Parents and guardians left out of the decision-making process have been at a loss for how to help their child when they come into contact with the system as result of their substance use. B.C. may be following similar legislation in place in Alberta.

Since 2006, Alberta Protection of Children Abusing Drugs Act has implemented law that, according to the Alberta Health Services website, is a “Protection Order...your child will be taken involuntarily to a Protective Safe House for up to 15 days for detoxification, stabilization, and assessment.”

If B.C. is proposing a similar model, we need to critically question whether the strategy has been thoroughly studied over the last 14 years. Has it shown long-term benefit, or is it causing more distress, lasting trauma, and mistrust of the healthcare system among youth?

Transparent analysis is needed from the (minister) about the risk and benefits of this proposed change, along with consultation with those who will be most impacted. The voice of youth being affected must be included. There is also a need for healthcare clinicians who work with the youth who use substances to question and call for research on this strategy.

We need specific criteria and measurements of successful health outcomes. We need to know if, in fact, it is an evidence-informed option to complement other long and short-term options for youth with substance use issues or a reactive stop-gap measure that may do more harm than good.

Jessica Key and Michelle Danda are mental health and substance use nurses.