In the grand story of the Titanic, it may seem that all that can be said has been said already: the sinking of the great ship has held the collective interest of the world for a century now, its story being told and retold through films, books and reams of historical research so extensive it may seem that there are no mysteries left to uncover.

And yet, as the 100th anniversary of the sinking of the Titanic approaches, there are still unknown details about the people who lost their lives - or barely escaped - on the night of April 15, 1912, and an appetite among the public to learn more about one of the most famous events of the 20th century.

The fascination with the Titanic makes perfect sense to Scott Larsen, a freelance journalist who has spent the last few months immersed in the story.

"It has everything in one historical moment: it has rich, poor, it has hope, it has love, it has grief," he told The Record. "And it's a puzzle, with pieces to fit together. It's totally pulled me in."

And he's not alone in that. "The three most-written about topics in the world are, first, Jesus, then the U.S. Civil War and third is Titanic. It absorbs people," he said. "I think it draws you in, in different ways - if you're interested in ship building, in maritime history, in people, in the story of immigrants. It's all there."

Larsen, a New Westminster resident, has been working on a six-part series about the ship and her Scandinavian passengers for the Den Danske Pioneer, an English language international Danish newspaper published out of Chicago, for the last few months.

The commonly held belief - buoyed, no doubt, by the 1997 James Cameron epic Titanic - is that the passengers, aboard the ship were predominantly wealthy English and poor Irish, with just a sprinkling of Americans and Europeans of various nationalities among them.

That isn't quite accurate.

In fact, says Larsen, Scandinavians made up a bulk of the passengers and yet their stories have remained largely unheard.

"The top three were the British and American - about 300 each, and those were mostly the upper class who simply wanted to ride on the maiden voyage of the Titanic - and then as a group, the Scandinavians were the third largest (group)," he said.

Scandinavians include those from Finland, Denmark, Norway and Sweden.

"There were more Swedes than Irish," he notes.

Those stories - the lives and often deaths of the 13 Danish, 31 Norwegians, 123 Swedes and 65 Finns aboard the ship - are what Larsen hopes to share with readers of the Pioneer.

And, on April 1, he'll also be sharing some of those stories at the Scandinavian Community Centre in Burnaby.

The story of the Titanic is so familiar to most in North America that the basic details need little reiteration: the ship left Southampton on April 10, made stops on the coast of France and then Ireland, and finally headed off for New York across the cold Atlantic.

One hundred years ago this week, the lifeboats - of which it would later be learned there were not enough - were being tested; final fittings were deemed complete throughout the ship on March 31.

With less than two weeks till it was scheduled to depart, there was still a flurry of activity going on to outfit it completely.

Its maiden voyage might have been over before it even began, with a close call as it left Southampton - the large wake it created caused another ship to pitch, breaking its rigging. The two ships came within just a handful of feet from touching.

But the minor crisis was averted and it set off, delayed by only an hour.

Among those who research the Titanic, there is still even now speculation about exactly what went wrong, and how.

Some details aren't in debate: at some time just prior to midnight on April 14, on a cold and clear night, the ship hit an iceberg, its hull breached in multiple spots which, given the design of the interior, made it impossible to stop the flow of water.

By 2: 30 a.m., the ship had sunk entirely - some 1,517 people had died, many of them still inside the third-class passenger area, and just 701 were still alive, awaiting rescue.

But how exactly had the ship hit the iceberg in the first place? How much did a desire for speed lead to the disaster - if at all? How did the iceberg get missed when crew were dispatched to watch for them and warnings had been sent to them from other ships? Why were some areas of the ship locked, as many have claimed, making it impossible for people to come on deck?

Some of those questions may never be fully answered, but the mystery - for Larsen - is part of the fascination, because it reveals so much about the people who worked and travelled on the ship.

History, he says, is always about the people.

"This story about the crew member up in the crow's nest who should have seen the iceberg - some have said he was drunk," notes Larsen.

"But one crew member got off in Ireland, and (it's possible) that he had in his pocket the key to the box that held the binoculars."

One moment of simple human error - forgetting a key in a pocket - may have been just one piece in the disaster's narrative.

But certainly not the only one: another problem was the visibility.

"It was the clearest night that anyone can recall - you read that over and over - the ocean was smooth, there was no moon out."

In rougher conditions, the water chop-ping up against the base of an iceberg will create a more visible line of white, giving a clue that something is ahead; in brightly lit conditions, icebergs are easier to see.

That, says Larsen, may have contributed more greatly to the eventual disaster than speed.

But there was - as in most great tragedies - no "one answer" to the question of the Titanic's sinking.

Of that, everyone is in agreement.

For the Scandinavians on board, their experiences in many ways echo what their fellow passengers would have experienced: either surviving the chaos to discover they'd lost family, or perishing altogether.

Almost all were immigrants - many would not have spoken English at all - and simply getting to the ship and paying for the ticket would have been a monumental task.

"First, you had to get permission to even leave your country, as an immigrant - and you got your ticket from a ticket agent in your country. ... For an immigrant in 1912, you made maybe (the current equivalent of) $700 annually, and a ticket on Titanic in third class would be about $650. ... First class could be as high as $60,000 to $80,000 in today's dollars."

Most Scandinavians were in second and third class; even there, in some ways, the Titanic was luxurious as it provided modest food for third class passengers. Most ships at that time required third-class passengers to bring their own provisions aboard for the entire trip - many simply did without.

Most of them were people seeking a new life in Canada and the U.S. - people with hopes and dreams for their future.

It's those stories that Larsen has unearthed to get a better picture of the fate of Scandinavians on the Titanic.

"One woman was going to Portland with her fiancé, brother and uncle - she was going to get married and get a farm. She was the only one that survived of her family.

Another survivor was Clara Jensen, a Danish woman who escaped wearing just a nightgown and an overcoat.

"Every April 14, she would stay up and she would have the nightgown folded up beside her. ... When she died, she was buried with her nightgown at her request."

Some survivors, he notes, fared relatively well, overcoming the tragedy to continue on with their lives.

Some did not do so well. "They would have nightmares, one committed suicide, one went into alcoholism. They just couldn't get their lives together, and they faded away into obscurity. Other people, by the grace of God, put it all together after such a traumatic experience and carried on," he said.

Still far too many didn't have the chance to recover at all, dying out in the Atlantic - Larsen notes that not a single nationality reached even a 50 per cent survival rate, and most were far lower. Of the 13 Danes, only two survived.

Larsen himself was initially drawn to the story after learning that his grand-father had come to North America in the early 1900s, settling in North Dakota as an 11-year-old boy, after travelling from Denmark with an uncle on board the Oceanic - the sister ship to the Titanic.

He later heard a chilling story from his stepmother: her godmother had been scheduled to come over from Manchester aboard the Titanic, but the family changed their tickets at the last minute.

"The father had a sinking feeling maybe they shouldn't go on the first voyage," said Larsen. "When they crossed over the Atlantic on the next ship, she could remember seeing the floating wooden deck chairs still there."

Bodies were found for weeks afterward, though many were never recovered. About 300 are buried in Halifax, notes Larsen.

"It was really a tragedy, it really affected people," he said.

And that continues to this day. "I've had to get up and leave the computer - you're dealing with death and dying. ...

"To think of it: for many there was a language barrier, they couldn't speak English, and some just didn't believe that the ship was sinking. There must have been pandemonium. ... As well as Hollywood can tell a story, it can't touch anything you can find in the history books."

Larsen will be sharing some of that history during a talk at the Scandinavian Community Centre in Burnaby on April 1, as part of Nordic Spirit 2012: The Lives They Left Behind, a two-day series of sessions on Scandinavian history and heritage. To find out more about the event, call the centre at 604-294-2777.

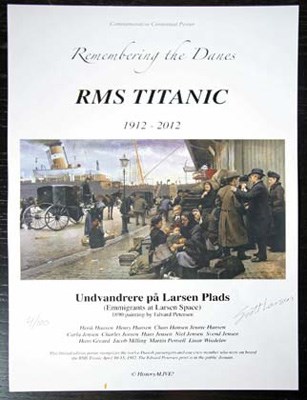

Larsen has also designed a series of five posters - one each for the four Scandinavian groups and one representing all four - commemorating the passengers on the Titanic, in honour of the 100th anniversary of the Titanic's sinking.

The limited edition, signed posters will be available at the talk, or by contacting Larsen directly at [email protected].

www.twitter.com/ChristinaMyersA

Check www.RoyalCityRecord.com for breaking news, photo galleries, blogs and more