“Have you ever heard of Turtle Island?” asks James Groening over a phone call. Like this reporter, most people, Groening confirms, have no idea where it is.

“As it turns out, we in North America live on Turtle Island,” he says.

Before you pull out Google Maps on your phone, know that Turtle Island is a native legend. However, if you look at a topographic map from a certain angle, North America does coincidentally look like a turtle, says the Burnaby-based artist.

Don’t see it? Groening will be at the Century House in Moody Park tomorrow to help you not just spot the Turtle Island, but also draw a strikingly colourful turtle based off of the legend.

But what is the legend anyway? It starts off with a calamity. The Creator, unhappy with all the negativity and violence in the world, decides to press the refresh button, and floods it, explains Groening.

A small group of survivors — a spiritual man, a turtle, a loon, a helldiver (red-necked grebe), and a muskrat — manage to convince the Creator to recreate a habitable land, as goes the legend, says Groening.

Though a simple story, Groening points out that it's steeped in morals about second chances; and how even a little being can effect big change.

Legends such as Turtle Island often present themselves as dramatic artworks in Woodland art — a school of art that's common to East Central Canada, and popularized by native artist Norval Morrisseau in the ‘60s.

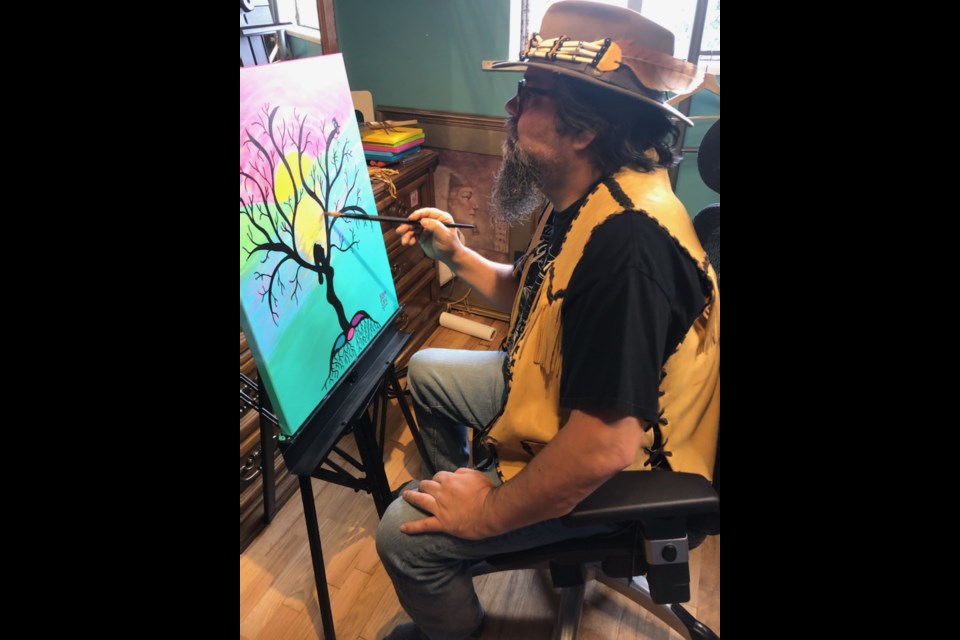

Groening's artworks follow this style.

Groening was introduced to Woodland School of Art while in pursuit of learning more about his cultural roots.

“I grew up in a white environment (Groening was adopted by his white grandparents), so I never had that connection to my native roots."

Art is helping him close that gap.

A 60’s Scoop (referring to the period when Indigenous children were separated from their families to be put into the child welfare system) survivor, Groening grew up disconnected from his Kahkewistahaw roots.

He was adopted by a white family, and only met his biological mother in his late ‘20s. “I was always told that she left me and ran away. But then I learned about the 60’s Scoop, probably about six years ago.”

That made him think: “Maybe the scenario isn't quite what I thought it was. And then, with the 215 discovery (referring to the discovery of mass graves near a residential school, in 2021), I became more curious — I suppose I felt a little more responsible to do something.”

Groening, who grew up in Manitoba, says it was quite a hostile environment to be a native for most part of his life.

“When I was a kid, also most of my life, whenever I heard the beating of the drum, I would always want to walk the other way, because I felt ashamed.”

He recalls getting into fights with those who picked on Indigenous people like him. “I was the only Indian in town pretty much, so I was fighting all the time.”

Now 54, though he still sees a ton of negative comments directed against native people on a daily basis, he is also aware that things are changing for the good.

Healing through Woodland art

Groening wants to add to the momentum.

“I'll try to do my part. And that is through trying to explain some traditions, cultures and realities,” he says.

While accepting the pain that his ancestors had to endure, Groening is now more interested in moving the dialogue forward with questions like: What do we do now? Where do we go from here?

And a way to start this conversation, for Groening, is through art.

His first attempt to draw was a few years ago, when he tried to recreate the drawing of a Haida (a style practised by an Indigenous group of the same name) hummingbird.

At that point in his life, he wasn’t in the best of health, and just wanted to take up drawing in the hopes of feeling better. Before turning to art, Groening worked with a company that built equipment for mining.

The bird came out well, so he drew a few more. At some point, he decided to paint originals rather than copying stuff.

“But what is my stuff?” he wondered.

Not long after, he came across the painting, The birth of Norval Morrisseau by native artist Mark Anthony Jacobson at another auction. Groening was drawn to the style, and reached out to Jacobson with the request to teach him how to paint.

What followed was an apprenticeship under Jacobson (through a grant from First Peoples' Cultural Council) that initiated him into Woodland art.

Though Groening has only been painting since September 2021, his art has become wildly popular.

He has seen interest from New West Arts Council and Vancouver-based Skwachàys Lodge Aboriginal Hotel and Gallery; and has been offered a one-week residency by Artscape, in Toronto.

Currently, he is also gearing up for a big show in Vancouver-based Massy Arts gallery that will explore his life’s journey through artworks which convey endurance, positivity, and most importantly, inclusiveness.

“Once in a while, I paint a bunch of leaves and make one leaf a different colour. Just to make people question,” says Groening.

What he hopes they realize is that “we’re all connected. And it's not just people we're talking about, our environment too.”

James Groening's workshop, organized by Arts Council of New Westminster, will take place between 1 and 3 p.m. at Century House, in Moody Park, on July 21. All supplies will be provided.