When Judy Darcy entered politics, it’s unlikely she envisioned a day she’d see someone brought back to life after overdosing on drugs.

But that’s been part and parcel of the New Westminster MLA’s job as B.C.’s Minister of Mental Health and Addictions. Since taking on the role in July 2017, Darcy has toured the province to get input on how to improve a “broken” system for folks with mental health and addictions. She has visited youth treatment centres, recovery homes, a homeless camp in Surrey, youth hubs, a First Nations health centre, safe-injection sites and countless other programs along the way.

The Record had a chance to chat with Darcy about the new Ministry of Mental Health and Addictions. The following excerpts from that conversation, transcribed by theRecord, have been condensed and edited for clarity.

In July 2017, you anticipated a “huge challenge” when you were appointed as the minister of mental health and addictions. What has that journey been like?

We are a start-up, but we are a start-up that is trying to create a better system for mental health and addictions, at the same time that we are dealing with the biggest public health emergency in decades. Over 1,400 people died last year from all walks of life, all corners of the province, including, I think the latest numbers are about 22 deaths in New Westminster.

What is your mandate?

To build a better system for mental health and addictions, while this (overdose crisis) is going on. So my immediate focus has been on the overdose crisis, but, at the same time, we are embarking on plans for what that looks like, and that, of course, starts with talking to people who have experience in the system with mental health and addictions.

What have you learned?

Everybody has a story, which is not surprising because one in five British Columbians – that means one in five people who live in New West – are struggling with a mental health issue. Some mild, moderate, some more severe. But one in five. A slightly smaller percentage are dealing with addictions, but addiction affects every single family. Every family, including my own.

What is your family’s experience with mental health?

My mother struggled with mental health and addictions in her adult life. I know what the stigma is like around that because I grew up in a small town in Ontario and you didn’t say your mom was in a psych hospital. I grew up in Sarnia, Ontario – I was born in Denmark but grew up in Sarnia. If you said she was in St. Thomas, which is where the big psych facility was, that would be like saying she was in Riverview. You know? So you didn’t say that. We pretended she was in an acute care hospital. She just kept being admitted and released. It wasn’t talked about. That was a while back, but stigma is still an enormous issue.

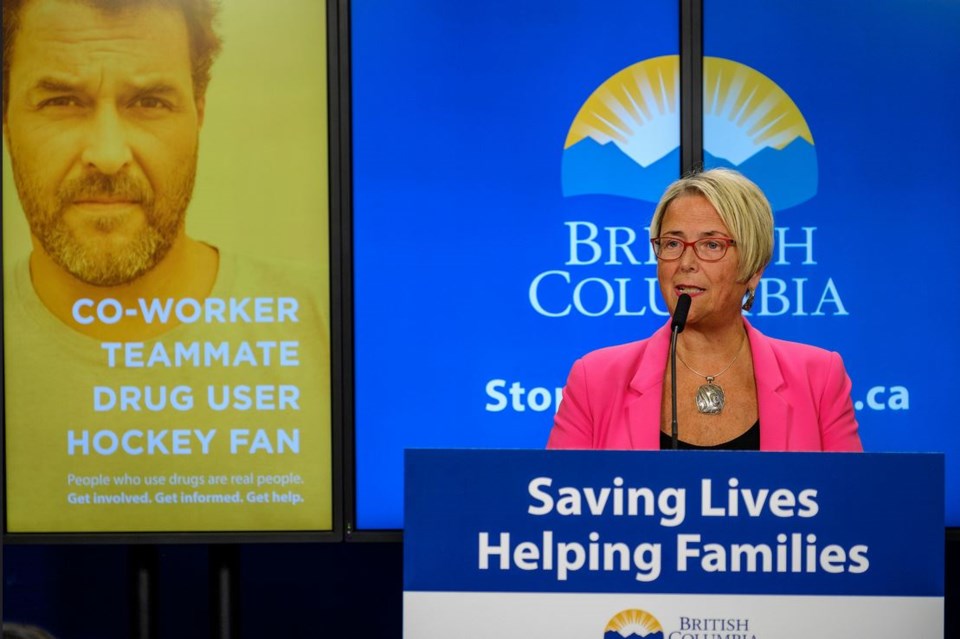

One of your ministry’s announcements centred on an advertising campaign with the Vancouver Canucks regarding the stigma surrounding addiction. Tell us about that.

The purpose of this ad campaign is to combat stigma by saying to people, very powerfully, this affects everybody. And it is right across the province. Vancouver and Surrey and Victoria have the most deaths by overdose but it’s Abbotsford, Chilliwack, New Westminster, Kelowna, Kamloops, Prince George, Duncan, Nanaimo. It really is everywhere and it really is people from all walks of life. The figures I have seen say 17 per cent of the people who have died by overdose are homeless, so that’s 83 per cent who aren’t homeless. The majority are not, and the majority are people who are using alone at home. They die because they are alone. Well, they die because the drugs that they are addicted to are laced with poison and because they are alone and there is no one there to revive them with naloxone. Stigma means people use alone and people are afraid to seek help. So stigma is a big factor, both in the deaths but also in people not seeking help for mental health and addictions.

The Record regularly receives press releases from your ministry about announcements such as making naloxone more available, addressing stigma or expanding services. Can you describe the approach you have tried to take?

We have to be bold and innovative because four people a day are dying. We are escalating in many different ways. There are more harm-reduction sites across the province. …There’s a thousand locations now in B.C. where you can get naloxone kits, including hundreds of pharmacies. We have expanded access to life-saving medications. The coroner said to me when I met with all of her senior coroners, if it weren’t for the poisoned drug supply, we would have had about 300 deaths by overdose. The overwhelming majority are because the drugs are contaminated with fentanyl or carfentanyl.

Why make prescription medications, such as methadone, and naloxone, which blocks the effects of opioids, more readily available?

If people are addicted, in the short term they have to be able to have safe prescription medication as opposed to poison. If we don’t do that, people will die, and you can’t possibly get on a pathway to treatment and recovery if you’re not alive. The first step often, if you can save somebody’s life, and we are trying to do that with access to naloxone and more people trained, we need to be able to connect them with treatment. For a lot of people that means suboxone, methadone or some other safe prescription medications that are alternatives to street drugs. Then connect them with longer-term treatment and longer-term recovery. But they have to be alive first.

The ministry has created an overdose emergency response consisting of a provincial centre and regional teams that will prioritize efforts to address the overdose crisis. What’s this all about?

It is a public health emergency. I have said we need to treat it that way. We know how we respond to wildfires, we know what we would do if we had an earthquake – we have emergency response plans, so we said we are really going to treat this like a public health emergency. … I think we are truly treating it like a public health emergency and we are pulling out all the stops – as we should. There are more people dying from overdose than from any other single cause – vehicle accidents, you name it. It is staggering. So we are doing more, we are doing it in more communities, we are involving more people, we are really trying to build it on the ground in those communities across the province. I think we have really escalated our response considerably.

How would you describe the system for mental health and addictions?

We have a system for mental health and addictions that is broken. It is confusing. It is fragmented. It is uncoordinated. There are big gaps. People work in silos. So it’s a real challenge connecting people with the treatment and the services that they need, which is why my mandate is to build a better system for mental health and addictions, a seamless, coordinated one, focusing on child and youth mental health initially – and the overdose crisis, of course, which was the urgent priority. So it’s a real challenge to deal with an overdose crisis of this magnitude, a public health emergency of this magnitude, with a system that is in many ways broken. … That’s not going to get fixed overnight. My mandate over a number of years is to build that better system. I think mental health and addictions have been the poor cousin in the health-care system for many, many years. Within that addictions is the poorer cousin. That’s not saying that the mental health system is in good shape. Because it’s not. In the coming months we are going to be working on a plan for building that better system for mental health and addictions.

In your role, you must encounter some pretty heartbreaking situations. Have you cried?

I have cried. I have cried many times. If I don’t cry when I am out there, I sometimes cry when I leave. But what I have learned to do over the last seven months, I’m learning how to take people’s stories and have them fuel my passion and my drive to make things better. The death toll, people sharing their stories about their loved ones. People email, write and phone a lot. I try and make some time every week to call one of those families and to hear their stories. It’s important for people in government to know what this is like for families. They are losing loved ones. That’s what drives the change that we are making. And those families really need to be able to share it, and they need to know that somebody is listening.

Are any of the initiatives you’ve introduced starting to make a difference?

In the overdose crisis, it’s too early to say. The coroner would say it’s too early to say. The chief medical officer of the province would say it’s too early to say. We did not see a spike as we entered the winter months this year, and we were worried we would. But it’s only February now, and we won’t really know until we are out of the really bad weather. Because bad weather means people go inside. People don’t mainly die on the street, they die when they are using drugs alone. Bad weather drives people inside, which is why there is usually a spike. There was, last year, a huge spike in the winter months. There has not been a spike in the winter months, it’s more leveled off. But it’s too soon to tell. There’s no question more lives are being saved with naloxone – tens of thousands.

Have you seen it being administered?

I have. It was my first week on the job. It was Day 4. I was at an overdose-prevention site, and the volunteers there called out that whatever his name was was overdosing. I asked them if it was OK for me to watch because I didn’t want to be an overdose tourist or voyeur, you know. They said, ‘No, of course.’ I saw these volunteers bring somebody back to life with naloxone, and then the mask. They called 911, but the person had been revived. The fire truck came first, then the ambulance. I’ve seen naloxone administered in Surrey as well. It just makes you realize how fragile life is.

What have you learned from talking to people on the frontlines of the overdose crisis?

When I say it could be any of us, really it could. I’ve met several people who were injured workers. In two cases of people I met the first week, one worked in forestry and one worked in construction. It began with a workplace injury and prescriptions. … There are many causes of addiction. It is very complex. In a lot of cases it’s childhood trauma, it’s mental health issues. In the case of indigenous people it’s about colonization and racism, residential schools. Indigenous communities are being affected. The overdose deaths are three times higher amongst indigenous people so we are talking about trauma, we are talking about pain.

Aside from government, community agencies and health-care organizations, how can individuals help?

As individuals we all have a role to play. We are still dealing with a lot of stigma. If you know someone who is struggling with addiction, you need to be willing to have a courageous conversation with them. I encourage people to get a naloxone kit so that you can reach out to someone that you know or you think is struggling with an addiction to street drugs. Find a way to summon up your courage and show love and compassion, and let them know you are willing to be there for them, to support them. Find out about the resources that are available so you can help somebody on their journey because it is a lonely journey. Stigma is still a big barrier to people seeking care, and that applies to mental health or addictions. Mental health is still, for far too many people, seen as a weakness. ‘You’re just not tough enough, buck up.’ Addiction is seen as a moral failure. Both of these are health issues. The analogy I like to use is, if someone breaks their leg, you know what to do. You would take me to the emergency room, I would get X-rayed. I would see an orthopedic specialist. I might get a cast. I might get crutches. It might be recommended I go to physio. And I get sympathy, not stigma. If I am struggling with mental health or addictions, the path is not clear. And stigma stands in the way of people seeking help and getting help. Love and compassion makes a huge difference.

What new initiaives are underway to tackle the overdose crisis?

In the past three months, the province has taken a number of steps to address the overdose crisis in B.C. Here’s a sample of some of the initiatives that have been introduced.

November 2017: The province launches a new pilot study in Vancouver that will test whether making drug checking more widely available will help prevent overdose deaths. People can anonymously submit samples of street drugs to be analyzed for their chemical makeup.

December 2017: The B.C. government launches a new Overdose Emergency Response Centre to help save lives and support people with addictions. The provincial centre and regional teams will prioritize four essential interventions to save lives and support people with addictions on a pathway to treatment and recovery:

* proactively identifying and supporting people at risk of overdose – including screening for drug use by health-care providers, clinical follow-up for people at risk, fast-tracked pathways treatment and care, and connections to social supports like housing;

* addressing the unsafe drug supply through wider access to drug checking and substitution drug treatment, such as Suboxone and hydromorphone;

* expanding community-based harm-reduction services, such as supervised consumption and overdose prevention sites, and outreach and mobile programs that extend the reach of harm-reduction services; and

* increasing availability of naloxone at the community level and among those trained to use the lifesaving treatment.

December 2017: The province puts more naloxone into the hands of British Columbians by providing pharmacies throughout B.C. with take-home naloxone kits that will be free for people who use opioids or are likely to witness an overdose.

January 2018: The Vancouver Canucks hockey team the Ministry of Mental Health and Addictions join forces to combat the stigma around substance use so people can feel safe accessing the treatment and supports they need. The public awareness campaign seeks to discredit false stereotypes by showing that addiction affects people from all walks of life and encourages British Columbians to stop seeing addiction as a moral failure – and to view it as a health issue that deserves compassion snd support.

February 2018: The province provides 18 communities hardest hit by the overdose crisis with community action teams who will focus on four actions aimed at saving lives and supporting people with addictions on a pathway to treatment and recovery: expanding community-based harm-reduction services; increasing the availability of naloxone; addressing the unsafe drug supply through expanded drug-checking services and increasing connections to addition-treatment medications; and proactively supporting people at risk of overdose by intervening early to provide services like treatment and housing. The program is initially being established in Vancouver, Richmond, Powell River, Surrey, Langley, Abbotsford, Maple Ridge, Chilliwack, Victoria, Campbell River, Nanaimo, Duncan, Port Alberni, Kelowna, Kamloops, Vernon, Prince George and Fort St. John.

February 2018: The province announces it will provide the First Nations Health Authority with $20 million over three years to support First Nations communities and Indigenous Peoples to address the ongoing impacts of the overdose public health emergency.