A blue wedding dress, a package of birthday candles and a toilet may have nothing in common yet they all help tell the story of the City of New Westminster.

The New Westminster Museum is home to a collection of 36,000 items, from the tiniest strands of hair of a toddler who died in the early 1900s to a steamroller so large that it needs to be stored offsite. The artifacts range from the sentimental to the strange.

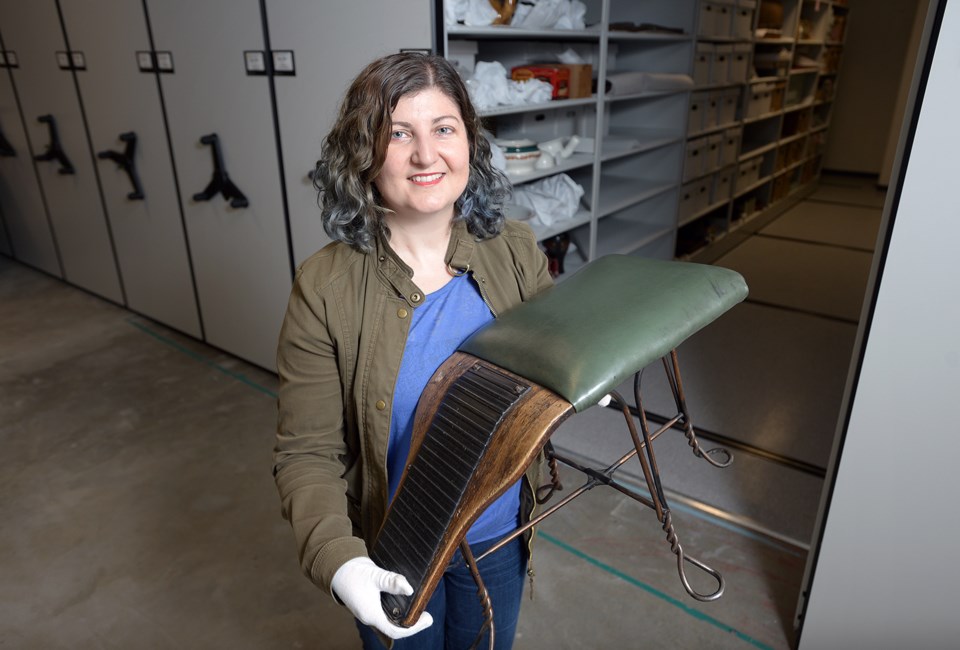

“What are the weirdest items I’ve come across?” ponders Oana Capota, curator of the New Westminster Museum. “We have a number of hair wreaths. Victorians used to collect their own hair, friends’ hair. When you look at it you can see people’s white hair, blond hair, red hair, dark hair. It’s woven into very ornate ornaments and put on display behind glass. That’s one of the weirder ones.”

Before accepting a piece into the museum’s collection, staff interview the donor and get them to sign a deed of gift and provide information about the item’s history.

“Our mandate is to tell New Westminster’s story,” Capota explains. “Where the value is for museums is things we can display for education, for research, but if there’s no information on it, it’s not helpful.”

The museum’s climate-controlled storage area is filled with shelves stacked with items such as typewriters, electronics, bars and toilets from cells in the old police station, and assorted attire, including a blue wedding gown from the 1940s that belonged to a woman whose husband was a soldier returning from war. Because they had limited funds, the couple, who spent seven years building a house in the Victory Heights neighbourhood, had a low-key wedding, and the bride wore a blue dress.

“It’s showing a bit of the social side. Not everything was good. They had a hard time,” Capota says. “That’s all she could afford – just a dress.”

The storage area also houses fragments of different buildings, including doors from the Chinese Benevolent Association.

“If you look at them, they actually look really boring. Not that exciting, kind of like other doors,” Capota says. “But this is the only thing we have from New Westminster’s two or three Chinatowns, these doors and a few other small items.”

The museum’s wish-list includes items from the city’s non-Anglo Saxon community, such as Japanese and Chinese citizens, and artifacts from the 1850s and beyond, when people started settling in the city. The city’s first museum was destroyed in the Great Fire of 1898, but Capota believes there’s a chance items still exist.

“Something always survives,” she said.

Although the museum is removing about 30 items from its collection, including trunks and sewing machines, that doesn’t preclude it from welcoming others in the future.

“The last time somebody called me in 2012 to donate a sewing machine, my first instinct was to say ‘No,’ but I talked to the lady. It turns out this was the sewing machine we wanted. It had so much history,” Capota says of an item that had been used in the 1930s and 1940s. “It was from the Chinese community. Right away my interest was piqued because we don’t have a lot from the non-Anglo-Saxon communities here in New West. Out of these 36,000 objects, I’d say 99 per cent are from that.”

Donations sometimes take a circuitous route to find their way to the New Westminster Museum and Archives.

The museum’s collection includes two logs dating back to the 1950s from the local Pacific Veneer plant. At that time, the mill would take the outer part of the log off to make plywood and sell the cores to people for firewood.

“This fellow who donated the items, he bought some to use as firewood around 1953. Soon after, he moved to Edmonton. He packed up his whole house and took the fire wood with him. In the 1990s they decided to move back to B.C., packed up the whole house and came back here. He saw my call for artifacts to do with waterfront work. He said, ‘I’ve been carrying these all over the continent since the 1950s,’” Capota says. “It was like it was meant to be.”

The New Westminster Museum starts planning its exhibits about two years in advance, considering themes that haven’t been done before, anniversaries that are coming up, artifacts that haven’t been displayed and stories that haven’t been told.

When items aren’t on display, people can make arrangements can be made to view specific items. The family that donated a television pops in periodically to check it out.

“We have family members that decide to come once every few years to see their item if it’s not on display,” Capota says. “We have the first television in New Westminster from 1948. The family members come occasionally, they have a look at it.”

Last year, Capota received a call from a senior in Vancouver who was downsizing. She’d inherited some items from a good friend who’d lived in New Westminster years ago and wondered if any of the items, including a clock that had been made in New West, were of interest to the museum.

“When I went over there, she showed me these other things. One of the sweetest things was a little box of candles that had been used. It was from this man’s birthday in 1932, I believe. He kept the candles and wrote the date and wrote ‘I had such a great birthday’ or something like that and put it in the box. We know exactly when the candles were used,” Capota says. “I’m happy to think that this woman was his best friend and, even now that this woman is going into a home, his memory will live on through the museum in one way.”