The growing list of large retail chains either drastically retrenching or going out of business has sparked speculation that physical stores could be headed for extinction.

Online shopping is touted as the assassin — a phenomenon that has allegedly poisoned the marketplace and made operating a bricks-and-mortar business untenable.

“That’s a myth,” scoffed retail analyst, and CEO of the retail consultancy DIG360, David Gray.

Yet Gray has been watching while a steady stream of dominoes topple.

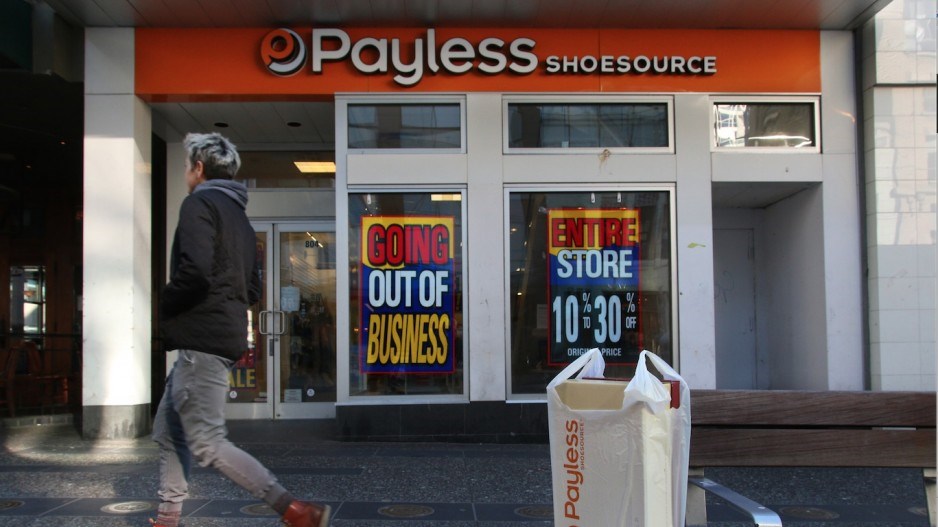

Payless ShoeSource Inc., for example, announced in late February that it plans to file for creditor protection in Canada and the U.S. and shut down its e-commerce operations and all 2,500 of its North American stores this spring. That includes 31 stores in B.C.

Two days later the Hudson’s Bay Co. announced that it would close all 37 of its Home Outfitters locations, including five in B.C.

Among the other chains that either have recently closed or are closing all Canadian stores are Crabtree & Evelyn, Rockport and Gymboree.

Other chains, such as Lowe’s Cos. Inc., are substantially reducing their retail presence.

“Radical change is going on, for sure,” Gray said, before explaining that acknowledging a changing landscape is different from forecasting the end of physical stores.

About 90 per cent of all retail sales still take place in bricks-and-mortar stores, and while the growth rate for sales is much faster in the online world, sales overall in bricks-and-mortar stores still trend upward.

“Amazon is opening stores,” Gray said, pointing to the e-commerce behemoth’s foray into Amazon Go grocery stores, of which there are now 10 locations.

Amazon also bought Whole Foods and launched Four Star stores, which sell items that consumers have ranked as four stars or more on the Amazon.com website.

Gray likened the recent flurry of large chain-store closures to a stretch of bad weather that does not necessarily equal a change in climate.

He pointed out that in the 1980s and 1990s there were spells where multiple large chains dissolved.

“It’s never been, in a given five-year window, always identical,” he said. “There have been growth periods and decline periods” in the number of large bricks-and-mortar retail chains.

Gray does, however, see rapid technological change on the horizon, and the area that he sees as being at the eye of the developing hurricane of disruption is supply chain logistics.

Analysts say Amazon may buy the large global shipper Fedex Corp., and Gray believes that it has plans to operate its own freighters for transpacific transport.

He predicted that logistics companies will become more integrated with retailers.

The partnership between the world’s largest bricks-and-mortar retailer, Walmart Inc., and Vancouver-based online food-delivery company Sustainable Produce Urban Delivery (SPUD) to offer online grocery delivery throughout Metro Vancouver is one example of the kind of partnership that Gray believes could become common.

SPUD created a subsidiary, Food-X Urban Delivery Inc., which delivers groceries to Walmart’s customers in Metro Vancouver. Walmart is in turn an anchor tenant in SPUD’s new 74,000-square-foot warehouse in Burnaby.

Gray said shared warehousing and distribution is one way that multiple bricks-and-mortar retailers could team up. Landlords, he added, could also be part of the puzzle, as mall owners could collaborate with retailers and distributors, which previously operated in separate silos, to work as a team to create the most efficient and popular use of retail square footage.

The best-positioned niche within physical retail, Gray said, is the one where operators are vertically integrated and manufacture their own products. Lululemon Athletica Inc. or Aritzia Inc. are examples.

Large stores that sell third-party brands’ products, such as Levi’s jeans, are likely to be hit hard, he said.

“I’m fascinated by department stores, because I think they are dinosaurs,” he said. “I’m so surprised that they are still around.”

Retail Insider Media owner Craig Patterson agreed.

Like Gray, Patterson believes the future of retail is in the “omni-channel” space, where businesses operate in physical and online environments.

But being in both sales platforms does not guarantee success. The key for a company that wants to operate a retail store is to have a welcoming environment that inspires shoppers, Patterson said.

“If a person were to go to a Payless store, why are they spending their time to go into an underwhelming retail environment when they could order something online and then go and do something more fun?”

In-demand products are also a vital element of any retailer’s future.

Patterson chuckled after describing Payless’ prank last year, when its representatives invited dozens of influencers to a party that was ostensibly to celebrate a brand of shoes named Palessi and designed by fictional Italian designer Bruno Palessi.

The influencers were later shown in YouTube videos saying how much they liked the shoes, and that they were willing to pay $400 or $500 for a pair that would have retailed at Payless for about $30.

“I went into a Payless store afterward and tried to replicate that in my own mind,” Patterson said. “Would I be fooled by this? I left and thought, ‘There wasn’t a pair [of shoes] that I would have worn if they had given them to me.’”

Click here for original article.